(from buzzfeed

by Michele Filgate)

Picador

The first thing I ever read by British writer Olivia Laing was her searing, haunting essay about loneliness and New York City that she wrote for Aeon Magazine. She’s currently working on a book called The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone. Her latest book is also very much focused on that state of isolation that all humans experience. The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking (Picador) tells us about alcoholism and creativity. Laing addresses her own childhood demons by focusing on six iconic American male writers who were alcoholics. She grew up in an alcoholic family. Instead of writing a straight-up memoir of that experience, she uses it as a jumping-off point and blends biographical information, travel writing, and cultural criticism into a compelling narrative.

She’s without a doubt one of the best nonfiction writers at work today. By merging empathy with curiosity, Laing brings a fresh perspective to whatever her current obsession is.

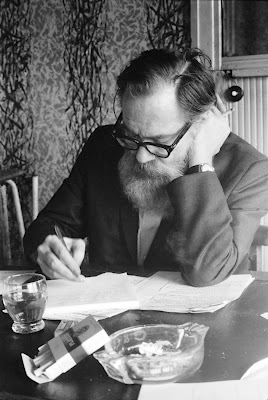

Jonathan Ring

So many writers, past and present, have been alcoholics. Why did you choose to focus on Cheever, Carver, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Williams, and Berryman?

Olivia Laing: I liked them, is the simple answer. I knew when I set out to write about alcohol and writers that I’d be dealing with very dark elements of their lives, and I didn’t want to produce what Joyce Carol Oates has described as pathography, or to be cruel and punitive, or to take pleasure in exposing them. So it was vital that it was people who I liked, and whose work I thought was extraordinary. That’s why traveling the physical landscape was so important too. All six of these men were deeply responsive to landscape, and wrote about it in very beautiful and heartfelt ways. It seemed to capture what was best about them, and I wanted to keep returning to that, as a respite or contrast to these incredibly bleak stories of drunkenness and degradation.

What is it about landscape that you’re drawn to? It’s definitely a theme in your first two books [To the River, a book about the river Virginia Woolf drowned in, and The Trip to Echo Spring] and the book you’re currently working on.

OL: Things happen in places. And when they’ve stopped happening, the place remains, though sometimes in different forms. Which means they’re ideal for a writer who is interested in assessing loss, which I guess is my true subject.

Is there a reason you stuck with American authors?

OL: I knew Tennessee Williams was central, because Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was the first thing I ever read about alcohol. And then I slowly sifted my way through the ranks of other alcoholic writers. It became clear pretty quickly that the story I was interested in was about America, about men and alcohol and writing in the America of the 20th century. There are no doubt other books that can and will be written, about different countries and different times. You didn’t ask directly about gender, but I’ll answer anyway: I stuck with men for a more personal reason, which is that my experience as a child was with a female alcoholic and the subject was just too painful for me. That’s a book I hope someone writes. Patricia Highsmith, Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras — such fascinating characters. But I didn’t have the necessary critical distance to do it. It leaves a legacy, fear in childhood.

It really does. But some might argue that what we’re afraid of is what we have to write about. Do you find that your fear inspires you but pushes you in a different direction?

OL: Hmm. I like writing about and am drawn to problematic subjects, things that are freighted with negative emotion. Maybe that’s a legacy of growing up in an alcoholic family, and also a queer but closeted family: a desire not to be in denial, to call things by their true names.

Ernest Hemingway John Bryson/Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

Do you feel differently about these scribes after spending so much time thinking and writing about them?

OL: I went through stages. Encountering the damage that alcoholics do, both to their own lives and to those around them, is grim, particularly if you have personal experience of it. There were definitely moments when I felt like I’d happily never read about Hemingway again. But then I returned to the fiction, and remembered why I was interested in them all in the first place. I definitely lost some of my affection for Raymond Carver after reading his first wife’s memoir. I hope the book isn’t judgmental, though. I didn’t feel judgmental. Sad, sometimes a bit sick, but also aware of how large a place circumstance plays in any — every — life.

I don’t think you ever come across as judging these writers. That’s one of the many reasons I loved this book. I’ve been thinking about how people write about addiction; how so often someone can just completely sidestep the realities and horrors of what addiction means. An excellent example is recent coverage of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death. The best pieces are the ones where empathy is involved. And addiction is such a loaded, emotional topic. What’s the best way to approach this subject?

OL: Yes, I’ve been thinking a lot about Hoffman and how incredibly punitive some of the responses have been. I don’t know about the best way, but it seems to me the most compassionate way is to assume that people are carrying a burden that you can’t see and that you have no idea whatsoever how heavy it is. But at the same time, resisting the temptation to glamorize.

I love how you weave together biography, travelogue, and memoir. Why do you combine all of these components? Are there other writers who inspired you?

OL: David Wojnarowicz, Sebald, Burroughs, Bruce Chatwin, Angela Carter, Derek Jarman. Woolf too, of course. Joan Didion, Anne Carson, Wayne Koestenbaum. I’m influenced by and interested in writers who break those rules about genre. But hybridization comes naturally to me. Writing a straight biography or memoir would feel very unnatural. For me, the pleasure of writing is finding the connections between fragments. I’m drawn to books that have multiple levels, that repay close reading, that go to unexpected places, that are formally surprising.

You’re an expert at finding the connections between fragments. Are you drawn to true stories or ideas or sentences? What resonates with you as a reader and writer?

OL: Big question! Stories, ideas, stray images, and words. When I’m working in archives or doing general research, I’m building a kind of image bank of scenes and encounters, which can be slowly pieced together. Bricolage, collage: Those are the arts that interest me. For example, with the new book I know that Andy Warhol’s corsets are important, and I know there’s a place for a little tin ambulance that was in the David Wojnarowicz archive, but I have no idea yet where they’ll fit in the book as a whole.

How much research went into this book? And at what point did you realize you had gathered enough facts and just needed to sit down and write?

OL: A lot. I worked in the Berg Collection at New York Public Library, going through the Cheever and Berryman archives, as well as digging through the various fictional works, journals, letters, and memoirs of all six of the writers I focus on. Biographies too, of course. And then research into alcoholism itself. My background is in medicine, but I didn’t know that much about the neurobiology of addiction, so I spent time with various scientists and researchers to get to grips with it. And I was researching as I was writing too. I didn’t find out everything I needed to know and then write the book. I like the surprises to keep coming.

John Berryman Terrence Spencer/Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

What made you switch from medicine to writing?

OL: Well, writing was always my first love. But I don’t regret the strange route that took me there.

Do you outline your chapters before you begin?

OL: Very roughly. I have a sense of the overall shape, but a lot emerges during research and in the writing process itself. I mapped Echo out on notecards on a huge board right at the beginning, but some of them were just stray lines and quotes. It helped with working out which bits would take place in which physical landscape though. That took a while to figure out.

You cite Lewis Hyde’s essay “Alcohol and Poetry” in which he says “four of the six Americans who have won the Nobel Prize for literature were alcoholic.” Did you find any statistics regarding alcoholic writers by country? Are American writers worse off than British writers, for instance?

OL: Alcoholism exists everywhere, though some cultures are definitely more affected than others. There have been an awful lot of British alcoholic writers, and Irish too. Kingsley Amis, Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice. But the myth of the alcoholic writer seems to me to a particularly American story. That was the story I was interested in investigating, anyway.

I’ve never thought of it that way. Do you think part of that myth has to do with Hollywood?

OL: Perhaps. I think it’s got a lot to do with Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and with Prohibition and the associated glamorization of drinking.

You say “writers, even the most socially gifted and established, must be outsiders of some sort, if only because their job is that of scrutinizer and witness.” I know your next book is about urban loneliness. What do you do, as a writer, to feel less alone? Why are you so drawn to the topic?

OL: Well, I don’t necessarily try and feel less alone. I got interested in loneliness as a subject because I started to notice the amount of fear and shame it generates. States like that are fascinating to me. And I felt like it had connections with creativity, with art, that it was often about difference and as such that it had a political dimension too. Loneliness is a state of lack, a longing, and though that can be acutely painful it’s also interesting. I do think that reading helps, maybe more than any other art form, in that it gives you this extraordinarily privileged access to the interior. It shows the reader other people also experience shameful, difficult feelings, which in itself makes one less lonely.

Perhaps it’s during this state of longing that we writers do our best work, if we aren’t bogged down by depression or addiction or self-loathing. I wonder how we can cultivate loneliness and use it to our advantage.

OL: I’ll tell you in my next book! Seriously, I think this is true, but like all those difficult states, I think there’s an art to dwelling there, and to maintaining the openness and sensitivity without getting overwhelmed by craving on the one hand, or just freezing up and closing off on the other.

John Cheever Paul Hosefros/Archive Photos / Getty Images

I’m kind of obsessed with loneliness; especially as it’s addressed in books, movies, and songs. Are you a fan of Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet? I feel like it’s the ultimate bible for those who have a melancholic nature.

OL: I guess mine would be Rings of Saturn, and through that Thomas Browne.

I love Sebald, but I haven’t read Rings of Saturn. Why did you choose that book?

OL: Actually, my favorite Sebald is The Emigrants, but Rings of Saturn is very much about melancholy, right down to the structure of its sentences.

What was it like to write about growing up in an alcoholic family?

OL: Hellish. Incredibly hard. There’s only really a few paragraphs about my childhood in the book, but the topic is — or was, anyway, at the time of — intensely personal. I wrote most of it in New York because I needed to get physically as far as possible from where I grew up, in order to break the taboo of silence and denial that almost all alcoholic families labor under. Which isn’t to say that my family wasn’t supportive of what I was doing.

I wondered about that. So much of this book is about the writers, but it’s also about your personal journey around parts of the United States as you try to understand them. Did you ever plan to devote more of the book to your childhood experiences, however painful they were?

OL: No. There’s always a balancing act when dealing with family material between telling the truth as you experienced it and respecting the privacy of those involved. And I didn’t want my story to be too loud in the mix, either. At the same time, it needed to be there to explain why I was so passionately invested in the subject, why I cared so much.

F. Scott Fitzgerald Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Do you find it easier to write about the biographical or the personal?

OL: I don’t find writing easy.

That’s a relief, only because I hate it when a writer says things like they don’t believe in writer’s block or they don’t struggle with getting words on the page. That doesn’t feel realistic to me. Writing is hard work. How do you navigate the ups and downs of the writing life?

OL: Oy. There are definitely good runs, especially toward the end of a book, but I mostly find it nightmarish. I’m trying to cut a lot looser now and just enjoy the research and trust that the words will find their way down. Also, it helps having been a journalist for so long — the stimulating power of a deadline has never failed me yet.

Would you ever write a straight-up memoir, or does that not appeal to you?

OL: Nope. I have no interest in straight-up anything. Boring. I like hybrid books, hybrid thinking. I wonder if this is about queerness too, with having grown up in a queer family, with having a sense of transness about my own gender identity. I’m not particularly drawn to the straight or the pure. In fact I find those concepts dangerous as well as aesthetically displeasing. I like the entangled, the tarnished, the dirty. Transgression is what appeals to me. Straight-up transgression.

Do you think the culture of drinking, in terms of writers, is just as bad as it always has been?

OL: Not at all. I think Echo is very much a book about the 20th century. As a culture we’re much more censorious now about drinking. Our addictions tend more toward pharmaceutical drugs and social media, online presence. I think it’s driven by the same factors — insecurity, loneliness, anxiety, social unease — but we choose different channels to gratify our urges, our needs.

Do you think social media addiction is just as harmful as alcoholism?

OL: No. I don’t think it breeds the kind of violence and chaos that we see with alcoholism. But I do think that it has consequences in terms of intimacy and attention. I don’t have an answer to this yet, really. I’m watching it closely. And I do think that it can be wonderful and connecting and a source of joy too. Though that’s true of alcohol, isn’t it?

How have your years as a book critic shaped you into the writer you are now?

OL: Well, I was an editor for a long time and I think that’s kept my writing tight. But criticism is certainly part of all my books. I’m fascinated by reading texts, and by ways of responding to them, especially ways that move between the emotional and the intellectual. I like digging around in the gap between the art and the life. I’m writing about visual artists now, for the loneliness book (Warhol, Wojnarowicz, Henry Darger), but it requires the same skills. I started out as a herbalist, back in my twenties, and I think there’s some commonality in those two roles — reading the body, interpreting the body’s symptoms, and reading and making sense of a text, an image.

At one point in the book when you’re talking about what alcohol does to a writer, you say: “You begin with alchemy, hard labor, and end by letting some grandiose degenerate, some awful aspect of yourself, take up residence at the hearth, the central fire, where they set to ripping out the heart of the work you’ve yet to finish.” Do you think alcohol is the biggest threat to a writer’s productivity, or self-loathing? Or a mixture of both?

OL: Lord, who knows. Alcohol is certainly a huge threat to the productivity of an addict, an alcoholic. But I do believe that self-loathing is a driver of addiction, alongside genetic inheritance. That said, I think almost every writer struggles against self-loathing and self-criticism. Most of the time, writing is against the odds. You have to keep producing words, against the odds.

No comments:

Post a Comment